1.2 Greek Cosmology and Philosophy

Shortly after the conquest by

Alexander in 331 BC, the Babylonian knowledge was transferred to the Greeks.

Accordingly, Aristarchus presented the first known model that placed the Sun

at the center of the known Universe with the Earth revolving around it, but

his astronomical ideas were rejected in favor of Aristotle and Ptolemy whose

geocentric model continued into the early modern age, until it was gradually

superseded again by the current heliocentric model due the efforts of

Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler in the 16th century.

Hipparchus and Ptolemy used

complete list of eclipse observations covering many centuries, compiled from

the Chaldean clay tablets recording all relevant observations of the various

relations between the periods of the planets. These relations that Ptolemy

attributes to Hipparchus in Almagest had all already been used in

predictions found on Babylonian clay tablets.

In the earliest Greek

literature we can find some references to various identifiable stars and

constellations. Among others, the Hyades and Pleiads star clusters, and the

constellations of Orion and Ursa Major, are mentioned in the Iliad and the

Odyssey by Homer, hinting a rudimentary cosmology of a flat earth where stars rise and disappear into the ocean. However, in Pre-Socratic

philosophy, Anaximander (610-546 BC) described a cylindrical earth suspended

in the center of the cosmos, surrounded by rings of fire, while the

Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus (480-405 BC) described the cosmos with

stars and planets circling an unseen central fire.

The word “planet” in Greek

means “wanderer” , because they were observed moving across the sky in

relation to the other apparently fixed stars. The five planets: Mercury,

Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, can be seen with the naked eye, in

addition to the Sun and Moon, to make a total of seven celestial objects that appear and disappear from time to time. Early Greeks thought that the

evening and morning appearances of Venus represented two different objects,

but Pythagoras (570-495 BC) is credited for realization that both were actually the same planet.

The Pythagoreans placed

astronomy among the four mathematical arts, along with arithmetic, geometry,

and music, while Plato proposed that the seemingly chaotic wandering motions

of the planets could be explained by combinations of uniform circular motions

centered on a spherical Earth. In his main books on cosmology, Timaeus and

the Republic, he described a two-sphere model and said there were eight

circles or spheres carrying the seven planets and the fixed stars.

In the 5th and 4th century BC,

many celebrated philosophers shaped the Classical Greek philosophy,

including Socrates (469-399 BC), his student Plato (424-348 BC) and his

student Aristotle (384-322 BC). The first was “the first who brought

philosophy down from the heavens, placed it in cities, introduced it into

families, and obliged it to examine into life and morals, and good and

evil.” Reale and Catan (1987). Plato was the most distinguished student of

Socrates, and the primary source of information about his thinking that he

presented in his dialogues. In his turn, Aristotle was also the most

renowned student who joined Plato’s Academy, though he widely disagreed with

him and criticized his theory of forms as “empty words and poetic metaphors.”

Prior (2016).

In the 3rd century BC,

Aristarchus, proposed a heliocentric model of the solar system, placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the known Universe, hence he is

sometimes known as the “Greek Copernicus” , but his astronomical ideas were

not well-received. In his only work to have survived, he calculated the

sizes of the Sun and Moon, and their distances from the Earth, but his

results are drastically underestimated.

In the 2nd century BC,

Hipparchus used the Babylonian observations and predictions to create better

geometrical models. He is considered among the most important Greek astronomers,

because he introduced the concept of exact prediction into astronomy, and he

was the last innovative astronomer before Ptolemy. Among many other

achievements, he developed trigonometry and produced accurate models for the

motion of the Sun and Moon, confirming the accurate values for the periods

of its motion that Chaldean astronomers are widely presumed to have

possessed before him.

The geocentric model was

predominant in ancient Greek philosophy as early as the 6th century BC.

This model puts the Earth at the center of the Universe, while the Sun,

Moon, planets, and stars, all circled around it in uniform motion. This is

the apparent view from the perspective of local observers who see the Earth

stationary, and the Sun revolving around it once per day, and also the Moon

and other planets and stars, although some of these objects also have their

own other motions. Furthermore, if the Earth is moving, we should observe

the shifting of the positions of stars due to stellar parallax, which means that the shapes of the various constellations should change

considerably from time to time across the year.

In reality, however, we do not

notice the relative motion of stars because they are much farther away than

Greek astronomers had ever thought. This stellar parallax was not detected

until the 19th century

after the inversion of modern telescopes. However, it might be appropriate

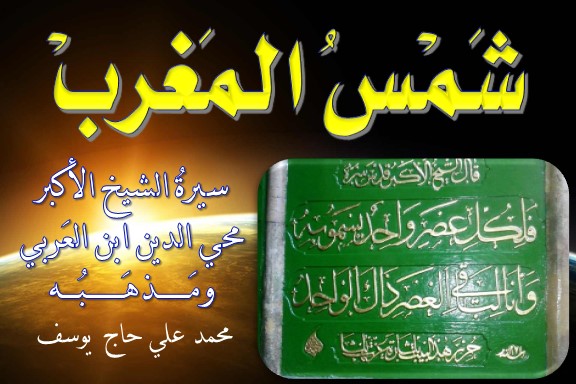

to mention here briefly, that Ibn al-Arabi declared clearly that the stars

are not fixed at all, and he correctly explained why we don’t observe their

relative motion. He also clearly affirmed that the Earth is moving and

rotating around its center, and explained why people don’t realize its

motion, as we quoted many of his statements in Volume I.

Plato described the Earth as a

stationary sphere at the center of the Universe, and the stars and planets

were arranged in circular orbits, starting with the Moon and up to the

celestial sphere of fixed stars. His student Aristotle added that heavenly bodies are attached to concentric crystalline spheres composed of an incorruptible substance called aether. Unfortunately, this concept of aether required it to have

ideal physical properties that could not be conceived in terms of modern

physics, especially after Michelson and Morley did not detect the aether

drift as it was predicted.

The geocentricism was well

established by the time of Aristotle, but the detailed model became standard

only in the 2nd century

AD, after it was developed by the Hellenistic astronomer Claudius

Ptolemaeus, or Ptolemy (100-170 AD) who wrote many important books on

astronomy and astrology, including: the Almagest, the Planetary Hypotheses,

and the Tetrabiblos.

In his most influential work,

Almagest, he explained how to predict the behavior of the planets, by

introducing a new mathematical tool called the equant. He gave a comprehensive

treatment of astronomical models and observations from many previous

mathematicians, and he placed the planets in geocentric order that would

remain standard in medieval astronomy until the 16th century when it was displaced

by the modern heliocentric system. The main reason why Ptolemy’s model was

successful is because he was able to explain the observed retrograde motion

of planets.

As they wander in the sky,

some planets slow down until they stop, and then they start to move backward

in retrograde motion, and then again they reverse to resume their normal, or

prograde, motion. In order to explain this, Ptolemy suggested that each

planet moved in epicycle at the same time as it rotated around the Earth, so

the planet moves around the epicycle, which in turn moves along the main

path in its original revolution, which is called the deferent.

This geometrical combination

of epicycles and deferents explained the observations mathematically, but it

was actually not real. Nevertheless, it convinced most astronomers for the

following fourteen centuries until the time of Copernicus.

Away from observations and

physical cosmology, Parmenides (in the late 6th or early 5th century BC) was the first

philosopher to question the nature of existence itself, challenging the

previous theories and establishing the “Eleatic School” of philosophers who

employed a method of axiomatic deductive arguments to justify their views that realty is one unchanging entity, and that

multiplicity, motion and change are deceptive phenomena. Some of his famous

successors in this metaphysical doctrine include: Zeno, Melissus and

Xenophanes.

In his single renowned work, a

poem called “On Nature” , survived only in fragmentary form, Parmenides

described his dual view of reality: “the Way of Truth” and “the Way of

Opinion” . In the first view, he explained that reality is one and

unchanging, and existence is timeless and uniform, unlike what we normally

observe in the world of appearances where our sensory faculties lead to

conceptions which are false and deceitful, hence the second view. This led

Democritus (460-370 BC) and other physicists to propose the atomic theory

of matter, to contradict these arguments.

Parmenides attempted to

distinguish between the reality of the unity of nature and its unreal

variety or multiplicity. He had immense influence on Plato, who named a

dialog after his name, and always spoke of him with veneration. In effect,

Parmenides’ monistic views were deeply characterized in the whole history of

Western philosophy, and he is often seen as its grandfather. In “Nature and

the Greeks” , Erwin Schroedinger identified Parmenides’ monad

of “the Way of Truth” as being the conscious self Schrödinger (2014), which

was an important part of the development of Quantum Mechanics according to

some interpretations, as we discussed in Chapter VI of Volume II.

However, Parmenides was not

able to convince other prominent philosophers, such as Socrates and

Aristotle, so his student Zeno tried again by reformulating the same argument

in terms of what to become known as Zeno’s paradoxes, that can be considered

the first thought experiments in which he demonstrated the deficiency of

both the discretuum and continuum views. Zeno basically showed that both

views will inevitably lead to infinity problems, which was in fact the main

motivation that eventually lead to the development of calculus by both

Newton and Leibniz as we shall see below.

We have already explained in a

previous book Haj Yousef (2018), that there exists some remarkable

correspondence between the metaphysical views of Parmenides and Ibn

al-Arabi. Parmenides’ philosophy of monism, together with the complex and

rigorous adaptation of his hypotheses in Plato’s Parmenides, constantly elaborated

by the later Neo-Platonists, offer even closer analogies to Ibn al-Arabi’s

overall ontological system, especially what came to be called later as the

oneness of being, that led to the Single Monad Model of the Cosmos. One of

the main principles of this eccentric cosmological model

is the “Re-creation Principle” which postulates that the cosmos is being

re-created every instance of time by the Single Monad, which alone may be

described by real continuous existence, while everything else are various

forms, or temporal imagery monads, brought into existence by this Single

Monad that takes only one form at a time. Despite the apparent undeniable

multiplicity of monads or forms, their existence ceases in the second

instance after their becoming, and is perpetually replaced by other, usually

analogous, forms. Therefore, Duality of Time, that results from the Single

Monad Model, can be thought of as a mathematical formulation of the Ibn al-Arabi’s Oneness of Being, which is essentially the same as

Parmenides’ monism that he expressed through his dual view of existence.

Zeno’s paradoxes of motion and plurality has been discussed at length in

Chapter II of Volume II.

As we mentioned above, Plato

is the founder of the Academy in Athens, and he is widely considered the

pivotal figure in the development of philosophy, along with Socrates and

Aristotle, his most influential teacher and student, respectively. He also

had noticeable influence on the Christian religion and spirituality, through

many of his followers such as Plotinus and St. Augustine, the early

Christian theologians and philosophers who played profound roles in the

development of Western Christianity and philosophy.

Plato himself borrowed some of

his main concepts from the Pythagoreans. He took their same mystical

approach to the soul and its place in the material world, and the idea that

mathematics and abstract thinking is a secure basis for philosophy. The

Pythagorean numerical principle, that all things in the cosmos are numbers,

can also be related to Plato’s view that the physical world

of becoming is an imitation of the mathematical world

of being, but this is also influenced by both Heraclitus and Parmenides.

Form the first, through his famous remarks that all things are continuously

changing, or becoming, as outlined in his well known image of the river with

ever-changing waters where no one can swim twice, and from Parmenides who

emphasized the idea of one changeless Being, and considered that change is

an illusion of the senses as we have seen above. These ideas of becoming and

being, led Plato to formulate his theory that there is a world of perfect,

eternal and changeless forms; the realm of Being, and an imperfect sensible

world of becoming that partakes the qualities of forms and their

instantiation in the sensible world.

Plato’s denial of the reality

of the material world is often coined as “Platonism” which means that the

material world is only a shadow of the real world, as neatly demonstrated by

the Allegory of the Cave, while the term “Neoplatonism” is applied to

Plotinus (204-270 AD) and his followers whose philosophy is based on the

three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul, that led to the cosmology

or cosmogony of “Emanationism” ; that all things in the cosmos are derived

from the “first principle” , as opposed to both creationism (ex nihilo)

and materialism (that all things, including mental aspects and consciousness, are results of material interactions). As Bertrand Russell

noted, Plotinus’ philosophy had a great influence on the development of

Christian theology:

“To the

Christian, the Other World was the Kingdom of Heaven, to be enjoyed after

death; to the Platonist, it was the eternal world of ideas, the real world as opposed to that of illusory appearance. Christian theologians combined these points

of view, and embodied much of the philosophy of Plotinus. ... Plotinus,

accordingly, is historically important as an influence in moulding the

Christianity of the Middle Ages and of theology.” Russell (1945)

The “first principle” for

Plotinus means a supreme transcendent “One” , containing no division or

multiplicity; beyond all categories of being and non-being. He identified

this “One” with the concept of “Good” and the principle of “Beauty” . Through

these concepts, Emanation can be considered as an alternative to the

orthodox Christian notion of creation ex nihilo. The first emanation

from the One is Nous, or: Divine Mind, Logos, Order, Thought, Reason, or the

first Will toward Good. From Nous then proceeds the World Soul, which

Plotinus subdivides into upper and lower, identifying its lower aspect with

Nature. From the World Soul proceeds individual human souls, down to matter,

at the lowest level of being and the least perfected level of the cosmos, as

he explained in The Enneads. These concepts are deeply characterized

in later Islamic Cosmology and particularly that of Avicenna and Ibn

al-Arabi.

Neoplatonism also influenced

many medieval Muslim scholars, from the 9th century, beginnings with Al-Kindi

(Alkindus, 801-873 AD), to the 10th and 11th centuries with Al-Farabi (Alpharabius, 872-951 AD) and

Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980-1037 AD). On the other hand, both al-Ghazali

(Algazelus, 1058-1111 AD) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126-1198 AD) vigorously

opposed the Neoplatonic views.

In general, on the concept of

time, we can detect two clearly opposing views in the contrast between

Plato’s and Aristotle’s schools of thought. Plato considers time to be

created with the world, while Aristotle believes that the world was created

in time, which is an infinite and continuous extension. Plato says: “Time

came into being together with the Heaven, in order that, as they were

brought into being together, so they may be dissolved together, if ever

their dissolution should come to pass.” (Cornford 1997: 99). Aristotle,

however, believes that Plato’s proposition requires a point in time that is

the beginning of time and has no time before it. This notion is

inconceivable for Aristotle, who adopts Democritus’ notion of un-created

time, and thus he says: “If time is eternal motion must also be eternal,

because time is a number of motion. Everyone except Plato has asserted the eternity

of time. Time cannot have a limit (beginning or end) for such a limit is a

moment, and any moment is the beginning of a future time and the end of past

time.” (Lettinck 1994: 562).

Therefore, time for Aristotle

is a continuum, and it is always associated with motion. As such, it cannot

have a beginning. Plato, on the other hand, considers time as the circular

motion of the heavens, while Aristotle said that it is not motion, but

rather the measure of motion, though he also relates rational time and

motion, but the problem that arises here is that time is uniform, while some

motions are fast and some slow. So we measure motion by time because it is

uniform—otherwise it can’t be used as a measure. To overcome this objection,

Aristotle takes the motion of the heavenly spheres as a reference, and all

other motions, as well as time, are measured according to this motion.

On the other hand, Aristotle

considers time as imaginary because it is either past or future, and both

don’t exist, while the present is not part of time because it has no extension

(Lettinck 1994: 348).

Ibn al-Arabi agrees with

Aristotle’s idea of a circular endless time and that it is a measure of

motion, but he does not consider it as continuum, as we shall see later. On the

other hand, he agrees with Plato that time is created with the world. In

fact Plato was right when he considered time to be created, but Aristotle

refused this because he could not conceive of a starting point to the world

nor to time. Only after the theory of General Relativity in 1915, that

introduced the idea of “curved time” , could we envisage a finite but curved time

that has a beginning. By this we could combine Plato’s and Aristotle’s

opposing views.